Profits we don’t understand are more dangerous than losses we do understand. Treasury produces financial benefits for organisations, by saving costs and by enabling the commercial activities of the business.

ARBITRAGE ADDER

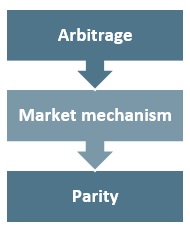

By contrast, chasing arbitrage profits is usually dangerous folly. Arbitrage is very important to define carefully and understand.

Temporary and risk-free

Arbitrage means dealing simultaneously in multiple markets, to exploit a temporary discrepancy in prices, and earn a risk-free profit.

Notice the arbitrage opportunity is both (i) temporary and (ii) risk-free.

NO FREE LUNCH

When markets are efficient, any short-term discrepancies in prices, giving rise to temporary arbitrage opportunities, are eliminated by the market mechanism.

Market mechanism

The resulting market condition of ‘parity’ is known as the ‘no-arbitrage’ pricing relationship. At the parity prices, there are no longer any arbitrage opportunities. Benefits and costs are equal. This is the ‘no free lunch’ principle.

Parity

WOLF IN SHEEP’S CLOTHING

Disastrous unauthorised speculation has often been misrepresented as ‘arbitrage’.

Treasurers need to understand arbitrage for two important reasons. We need to identify:

(a) Rogue trading and other breaches of policy, to eliminate them.

(b) ‘Too good to be true’ propositions, to decline them.

NOT ARBITRAGE

Let’s say interest rates in two currencies are:

|

Currency |

C |

D |

|

Interest rate |

1% |

3% |

Our boss asks us, “Isn’t this a great opportunity to borrow at 1%, deposit at 3%, and earn a risk-free 2% profit: why don’t we do it?”

Treasurers are often faced with this kind of question. We need an answer.

“UP TO A POINT”

This is a good way to start answers. It acknowledges the question is half-right. It’s certainly true that we could get an interest rate benefit by doing this deal.

But something important has been forgotten.

THE HIDDEN COST

There’s also a significant cost to the proposition. Namely, an FX loss.

We’d start the deal by borrowing currency C at 1%, and convert it to currency D at the spot FX rate. We’d simultaneously deposit currency D, to earn the attractive rate of 3%.

At maturity, we need to re-exchange the currencies. To avoid FX risk, we’d need to pre-agree a forward FX rate for the re-exchange.

If the market would ever give us a forward contract to re-exchange at the same FX rate as we enjoyed at the start, we could indeed be better off by the interest rate difference of 3% – 1% = 2%.

STING IN THE TAIL

But the market will never do that for us.

Market prices will normally already have adjusted, via the market mechanism, to eliminate any opportunity for risk-free gains by doing these types of ‘round trip’ deals.

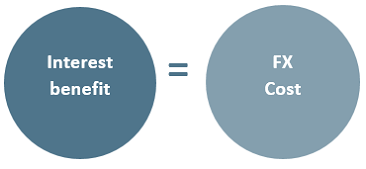

There’ll be an adverse difference between the spot and forward FX rates, resulting in an FX loss. Under parity, we lose exactly as much on the FX difference as we gain on the interest rates.

This is known as ‘interest rate parity’.

Interest rate parity

Having understood this relationship, we need to explain it concisely to others.

|

Let’s look at this example: Your new colleague has heard you mention arbitrage and interest rate parity, but does not understand what these terms mean. How would you explain the relationship between arbitrage and interest rate parity? Answer: Arbitrage means dealing simultaneously in related markets whose prices are misaligned, to take advantage of a temporary discrepancy in prices. Parity is the situation where prices are consistent. Under parity, there are no such risk-free profit (arbitrage) opportunities. Interest rate parity (IRP) is the expected ‘no-arbitrage’ price relationship between the interest rates in two currencies, and the spot and forward FX rates. In practice Most arbitrage opportunities are short lived and small, because the market mechanism acts very quickly to realign market prices. If IRP did not hold, a related arbitrage opportunity might be to:

In practice, IRP holds very strongly for widely traded currencies, because of the large volumes and speed of dealing, including arbitrage dealing. |

FICTIONAL PROFITS

Back in the office, hearing or seeing the word ‘arbitrage’ should alert us to be cautious and ask questions.

Nick Leeson of the former Barings Bank created unauthorised speculative positions, and misreported them as ‘arbitrage’ to his managers. Leeson concealed the losses on his speculations, and reported fictional profits.

HOW TO SAVE A BILLION

The reported profits were too good to be true. These fictional profits were large, persistent and reportedly risk-free. But no real arbitrage opportunity would have lasted that long. Senior management didn’t understand arbitrage well enough. As a result, they didn’t ask the right questions. Leeson’s disastrous speculations lost his employer well over $1bn, and led to Barings’ failure in 1995.

MY NAME IS CAUTION

Leeson recently sounded this warning:

“The message that my name brings is caution. You do need to understand what you’re doing, otherwise a lot of people blow up, and blow up very quickly.”

Nick Leeson, 2016

LESSONS TO LEARN

The official report into the failure of Barings included the following lessons:

(a) Management has a duty to fully understand the business it manages.

(b) Responsibilities have to be clearly established and communicated.

To fulfil our management responsibilities, we need to understand.

HOW TO SAVE $9BN

Were these lessons from the Barings failure learned and applied? Evidently not.

Subsequent rogue trading activity resulted in even larger losses, including:

- Société Générale 2006-08: $7bn

- UBS 2011: $2bn

A total of $9bn for those two organisations alone.

Invest study time to understand treasury as deeply as you can. Your organisation needs your insight to prevent the next disaster!

____________________

Author: Doug Williamson

Source: The Treasurer magazine